For three weeks in July / August 2016, I joined the UK-OSNAP research cruise on the RRS Discovery as an artist in residence. We departed Iceland for the Irminger Basin, spending three weeks at sea before returning to the UK. UK-OSNAP are part of an international collaboration working to establish a transoceanic observing system in the Subpolar North Atlantic to help better understand ocean circulation and its relation to climate change. You can find out more about my activities and response to the experience below and more about OSNAP on the DY054 cruise blog here http://www.o-snap.org/news-events/blog/

Return to OCEAN MAPPING

Late August 2016, Irminger Basin > Southampton, UK

Post 3: Assimilating circulation

The scientific events – instrument deployment and sample collection – took over a week of around the clock working to complete. Once done, we left the Irminger Basin area and headed back towards Southampton, signalling a different phase in the journey; science equipment was packed away leaving the deck freer for the crew to prepare it for dock and the scientists could exhale ever so slightly as their shifts returned to normal day time hours. For myself, there was a sense of growing urgency as I realised my time on the Discovery and for collecting material was limited.

When I arrived on the ship I had ideas, intentions and projections about what I might be interested in but mostly I had an open mind. At the start of the journey I was engaged in what felt like a crash course in oceanography, learning basic terms and theories to enable me to grasp the research and its approaches. I absorbed information from a wide range of sources without judgement or anticipation for where it would lead, lest it be limiting in the long run.

This led to some wonderful experiences. A chance conversation with a member of the crew led to them cracking a joke and suggesting that since I was an artist maybe I could help out by doing some painting below deck. As it goes, the idea of ‘painting the ship’ in actuality rather than a representation was very appealing. So, with a leap of faith, Duncan, took me below deck, showing me the waste disposal systems, water tanks, engine room, propellers and thrusters along the way, and shared with me his painting techniques.

Our task was to paint hazard lines; new regulations insist they need to be painted rather than using an old school style of tape. It was impossible for me not to connect the sharp masking taped edges, shiny gloss paint and the geometric design to an aesthetic of hard edge abstraction; masquerading health and safety legislation as a tongue in cheek site-specific artwork.

I’ve been thinking about the ship as a highly efficient organism whose interdependent systems are both frighteningly complex yet provide the stability and comfort that makes the ship so habitable. The water storage systems and circulation of water on board was of particular interest, not least because it connects to ways of thinking about ocean current circulation, which is the focus of the cruise. The types of water in circulation on the ship include ‘black water’, which is water from the toilets – sewage essentially, which is stored in a tank and treated with bacteria, and ‘grey water’, which is the water from the bathroom taps, showers and the galley and includes all the cleaning potions and bodily detritus like dead skin, hair and toenails. Apparently, the grey water tank is the most pungent smelling of the tanks, more so than the black water. Both these types of water are stored until the ship is a safe and legal distance out of port where it can be disposed.

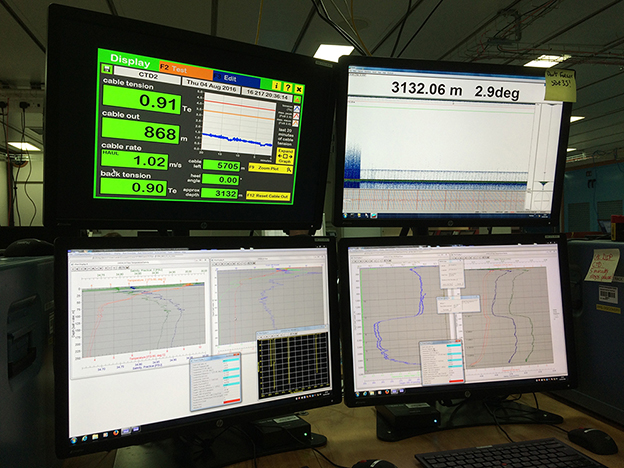

One of the challenges and excitements of the journey was learning about the research. It was like learning a new language; every question I asked led to a labyrinth of other questions that needed answering before we could return to the original question. I spent time listening and watching the scientists work and observing the equipment in action. To deepen my understanding I got more involved with the data and its collection and began to mimic some of the scientific processes, this included collecting my own data sets (of water temperature and salinity) live from the CTD computer screen whilst the instruments moved from the sea floor to the sea surface. Also, collecting my own water samples from the CTD, which collects water from depths ranging from 10 metres below the surface to around 6000 meters down, just above the seabed.

I was excited by the transience and inaccessibility of the sea water at these depths, for me it suggested an almost mythical quality; like a piece of rock from the moon, only more rare and infinitely less tangible. The properties of the water (its temperature and salinity) change very quickly once brought to the surface; whilst it still holds symbolic potential it ceases to be the thing it was. I wanted to find a way to somehow ‘capture’ it immediately and rather than storing it in a bottle (which I couldn’t help connect to Duchamp’s ‘Paris Air’) I began using the seawater from the different depths to paint with, using watercolour. I designed a colour key to indicate the depth, temperature and salinity of the water and plotted the data to build a visual stratification of the information. My data-plot was obviously much less precise than those created by the scientists, however it did visualise the different kinds of water passing through the area, from which the origin of the water and its current could be identified.

I also spent a lot of time taking photographs and moving image. In the middle of the North Atlantic from one day to the next, without land in sight, the view tends not to change dramatically and I have many seemingly repetitious photographs of the horizon line, weather and wildlife. The lack of dramatic change however perhaps builds a greater sensitivity to the small changes in the environment; shifts in the swell or bird life or a sighting of another ship on the horizon. Other subtle differences included indescribably beautiful sunrises and sunsets and in particular, whale sightings, which would dominate attention. In many of my photographs the blue, grey and green of the seascape is interrupted by the ship’s colourful architecture or science equipment, suggesting human presence but also bringing a sense of scale to the otherwise expansive wilderness.

I was expecting to feel a sense of loneliness at sea but I didn’t. For me it was a very a social experience, perhaps because I was trying to learn, meet people and be present when things were happening. Listening to people’s stories was a particularly joyful aspect of the experience and fed into my thoughts about storytelling about the sea in literature, such as Moby Dick (Melville), The Rime of The Ancient Mariner (Coleridge) and A Descent into the Maelstrom (Poe). Some of the stories that were told by crew and scientists have made their way into becoming audio recordings, which I am now (having returned) starting to transcribe.

One of the unusual and yet invaluable parts of the experience was being able to work in the lab alongside the science team. Whilst I was drawing, painting or writing the scientists around me were studying data, calibrating, making plots and preparing for science events. It was fantastically immersive and allowed me to absorb a huge amount of information; from knowing what was going on in terms of science events and data results, to seeing data interpreted in real time on the monitor screens. My proximity to the action embedded this new language more concretely in my understanding. It also meant that what I was doing, incongruous and out of place as it may seem, was visible and accessible.

After three weeks at sea we docked and disembarked in Southampton. The sun was shining and as we got closer to land I was hit by the smell of warm earth, rock and flowers and other things that I hadn’t realised I’d missed. The smell was powerful in its unfamiliarity, more so than the view of the approaching coastline. Back on land my legs did wobble (everyone asks) as my body physically re-acclimatised to solid ground but it’s taking longer for my head, which seems to still want to be out at sea. Luckily in some sense it still can be, as the next stage for me will be to start processing, editing, reviewing, assimilating and developing the material.

Early August 2016, Irminger basin, subpolar North Atlantic

Post 2: Instruments, events and watery depths

We have been at sea over a week; the weather is fine, I’ve dodged the seasickness bullet and am learning about life on the ship. All is well.

To provide some background, the focus for the scientists on this cruise (DY054) is to carry out a number of data capturing events. These often involve using instruments and equipment such as CTD’s, moorings and floats to collect data and water samples, which can later be analysed. All of these events are carried out in specific locations and many derive information from the ocean between the surface and the sea floor, capturing data on salinity, temperature, pressure and more.

Mooring recovery

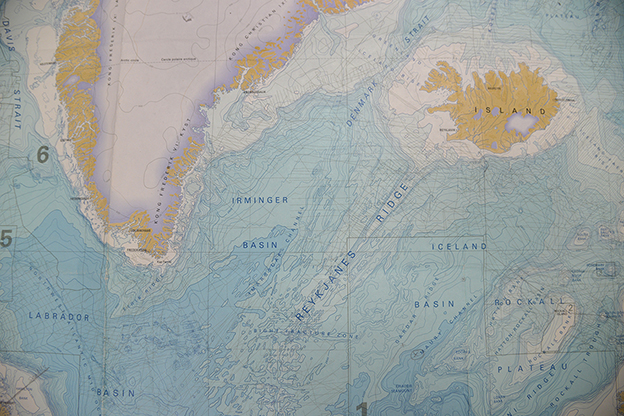

The mooring and CTD stations that we are visiting are on a straight-ish line between Greenland and Iceland, largely covering the Irminger basin. The moorings are done in the day and the CTD stations at night. All the scientists and many of the crew are on shifts so that the work can be covered over a 24-hour period, it’s a busy time and there is always someone around.

After leaving Iceland it took a few days to make it to our first CTD location near the coast of Greenland. We arrived just as dawn was breaking at around 5am to see icebergs and glaciers twinkling in the distance, barely visible in the cloudy hazy light, and red flashes from the lighthouse at Prince Christian Sound. It was a magical sight.

Greenland coastline

Soon after that, the first moorings began; M1 and M2 were recovered, having been underwater and actively collecting data for the past year. This is the first time OSNAP have returned to the moorings since they were deployed so bringing them to the surface and retrieving their data was an exciting prospect, as was seeing their condition for the first time since spending a year beneath sea level.

Recovering the moorings requires hauling them out of the ocean and removing and cataloguing the instruments. It’s heavy work and it’s cold out, plus due to the high pressure in the area the waves are rolling with more swell than the last couple of days, but the NMFSS technicians who are organising the operation have the process efficiently choreographed and everything ran smoothly. Once all of the M1 and M2 2015-16 moorings were out of the water (all of which were fine, with the addition of some biology to a few buoys) a reconditioned set were ready to go back in.

If you are not familiar with what the mooring’s are, let me try and explain: one mooring includes groupings of about four buoys incrementally attached along a long line of wire and between these groupings data collecting instruments are further attached. Many of these instruments look cylindrical and are made from a combination of metals to prevent corrosion. The wire is long – M1 was 2059m in length – at the end of the wire a heavy weight is attached, which is designed to sink to the seabed pulling the wire and the buoys down with it so the line and buoys float vertically upwards, securing the instruments for data collection at different depths. When it’s time for the mooring to return to the surface for data collection an acoustic release mechanism triggers the wire to detach from the weight and due to its buoyancy the mooring floats back up to the surface. M1, M2 and now M3 reached the surface intact and untangled, making it easier for a technician to catch it and draw it back to the ship.

To successfully drag down the buoys the weight needs to be significant, for the redeployed M1 and M2 moorings a small part of a massive anchor chain had been chosen. To give an idea of its scale, each chain link is about the width of my forearm. It made a dramatic sight when held aloft by the winch and hanging between the gantries before it was dropped to its watery grave.

In the evening, having completed work at moorings M1 and M2 the ship headed back closer to Greenland for more CTD stations and the launching of a number of RAFOS floats.

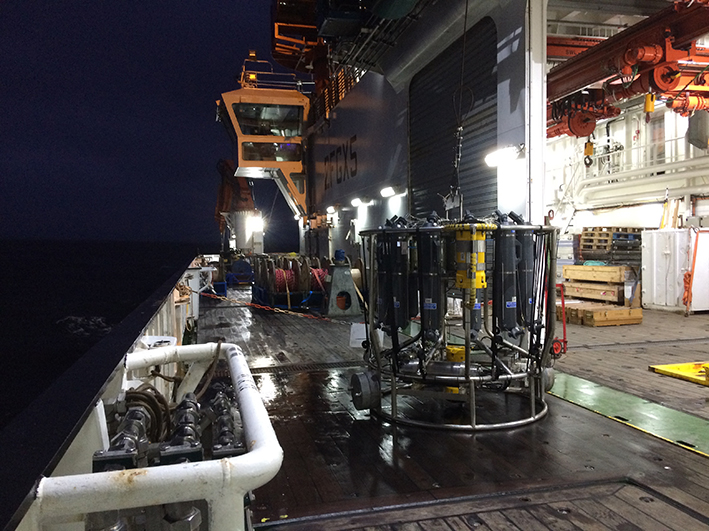

The CTD consists of a frame with a series of instruments attached to it, which is lowered to the seabed and then returned to the surface. As it comes up it collects water samples from specific depths from which salinity and nutrients can later be analysed. The CTD is an interesting looking piece of equipment and one that I have been spending a lot of time with. The notion of bringing sea water to the surface from inaccessible depths speaks of trying to capture something of the transience of the ocean currents, many of which are from different locations around the world and only temporarily in this spot.

CTD and ship in the early hours of the morning

The ship at night is very peaceful and although the ship lights are bright they are the only ones that can be seen in the darkness. I had expected that being in the middle of the subpolar North Atlantic I would feel at the mercy of the expanse of ocean around me, emotionally as well as physically and for the first few days I do. I can’t think too much about the vastness of space (and lack of solid ground) to my left, right, above and below lest a feeling of panic arise. However, this passes and perhaps because much of my time on ship has been spent with people, in comfort and focusing on the science, it protects my mind from wandering to the possibilities of what is outside.

But not entirely, as well as the science I’ve been learning about the engineering of the ship and how it sustains life in the ocean wilderness.

Last to mention here, is the social side of being on the ship; the science team includes researchers and students from around the world and the crew, many of who have spent much of their life at sea. Everyone has a story to tell and often at dinner these surface; from tracking polar bears and the different paces that glaciers melt, to ships meeting in the middle of the ocean to exchange salutations.

10.35, Tuesday 26th July, 2016

Post 1: UK-OSNAP research cruise, Iceland –> Greenland –> Southampton, UK

I’m in Iceland to join an international group of oceanographer scientists on their UK-OSNAP research cruise on the RRS Discovery. We set sail on the 27th July and will head towards the southern tip of Greenland, stopping at moorings in the North Atlantic along the way, then finally we sail back to Southampton for the 17th August. I am not a scientist, I make art (and other things) and this will be an entirely new experience for me – I’m as green as they come. However, thanks to Principle Scientist, Penny Holliday, from the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton I am learning about the project and its aims, which are “to make continuous measurements of the gyre and overturning circulation in the Subpolar North Atlantic”. It’s an international collaboration that will involve taking measurements for the first time ever from moorings in the Subpolar North Atlantic from Canada to Greenland to Scotland. Data from the project will help provide a better understanding of ocean circulation and its relation to climate change. The scientists write about it so much better than I can, you can follow their research, its aims and the OSNAP project and journey here – http://www.o-snap.org/news-events/blog/

So, what will I – a ‘fish out of water’ – be doing there? I hope to learn more about the project, its methods and the tools that enable it and the people involved, plus the impact their research might have. I am interested in what the lines of communication between our disciplines will be and I’m more than curious about the experience of being on a ship in the middle of the North Atlantic, with little internet, email access and no phone. My practice is often studio based but involves working in response to different environments and subjects; nothing so far will have been quite as extraordinary as this. Whilst on the ship I will be developing a new project, I’ve packed the watercolours and audio visual equipment but in truth it is hard to imagine what life on board will be like so inevitably I will be responding and nuancing ideas as I go, allowing the journey, physical and metaphorical, to influence what emerges.

So, I’m all packed and ready to go – I’ve borrowed a hard hat, steel toe capped boots and a boiler suit and I’ve got enough layers to keep me warm in a biting wind. I’ve also got Melville’s Moby Dick to keep me company. The only thing I’ve forgotten is a ball of string, which is apparently very important as everything needs to be tied down. However, I do have a roll of masking tape – from studio to ship – perhaps that will do the job.

I’m not sure how much access to internet I will have but I will be writing on here about the journey when I can…